Rickey Across Time

When Rickey returned to the United States in the early 1930s, he combined what he had learned in Europe with the social realism prevalent in American art at the time and worked his way across the country, painting still lifes, conducting portrait demonstrations at various colleges, and creating murals in public spaces for the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project. It was only after being drafted and serving in the Army Air Corps that Rickey began to move beyond painting. Following World War II, Rickey went on to study at the Institute of Design in Chicago, where he experimented with painting in various abstract styles. Wanting to push himself further while making use of his natural mechanical aptitude, Rickey also began to create sculptures, first out of glass, then plastic, and, finally, metal.

With rotors Rickey distilled a flower’s bud into its most basic geometrical elements. Moving away from depicting what was readily visible in nature, Rickey began to simplify the shapes he used to depict not the seen, but the unseen forces that drove his work. He began to work with lines or blades, sometimes one line alone, sometimes many lines in different configurations. As he wrote,

“Lines permit the most economical manifestation of movement I have found, a kinetic drawing in space.”

Rickey’s line sculptures are a combination of chance, provided by the breeze, and fate, controlled by the intricate engineering and craftsmanship that allows each line to move only as much or as little as the artist intended. It is no wonder that he titled one of his earliest series of line sculptures (begun in 1961) Atropos after the Greek goddess of fate and destiny. The two lines of Atropos IV depict the balance of the two competing forces inherent in all of Rickey’s sculpture–chance and fate. Column of Five Tapered Lines illustrates and then expands upon these themes by introducing the idea that a shape usually noted for its stability, in this case a column, can be simultaneously unstable.

Having settled upon his medium and his method, Rickey quickly added other basic shapes to his vocabulary, all while emphasizing that they were the means to an end:

“Since the design of the movement is paramount, shape, for me, should have no significance.”

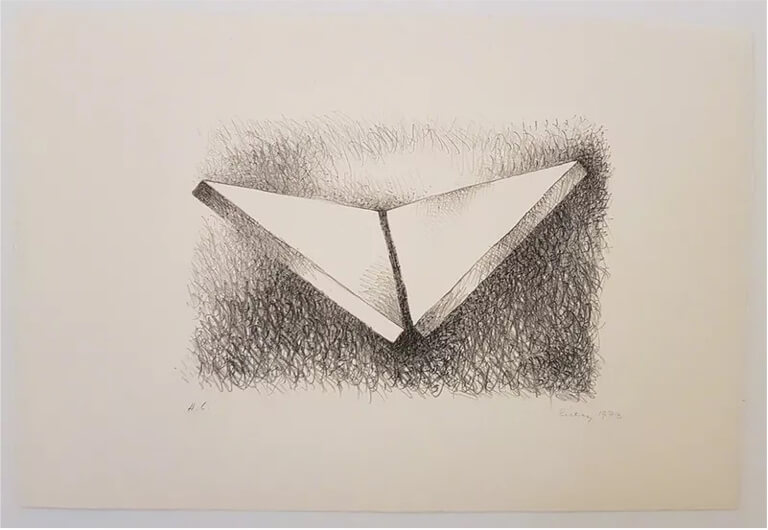

He explored the strength of triangles, adjusting the angles of each from piece to piece, thus finding another way in which to add variables to simple forms. The vertical equilateral triangles of Two Triangles come together to form a rhombus, while in the print Two Triangles Dihedral, Rickey places the emphasis on the angle at which the two horizontal isosceles triangles meet. In Cascade, Rickey has truncated triangles into trapezoids, which when stacked in sequence from small to large form another larger trapezoid. Rickey then further reduced the triangles to nothing more than angles in works like Conversation–Mondrian Meets Malevich.

%402x.jpg)

In addition to working with both sheets of metal and sheets of paper, Rickey also worked in wire, finding it sensitive enough to capture the slightest movement of air and supple enough to be used to create intricately detailed versions of simple shapes. It was also a medium with which Rickey could work in quiet, solitary moments, creating sculptures at a scale that did not require many studio helpers or loud machinery. With wire, Rickey could once again be the solitary artist. It is no wonder that he chose a portion of art historian and author Wieland Schmied’s 1981 poem “Freedom” to inscribe on his print of his wire sculpture Column of Eight Triangles with Spirals:

“We can remember

and we can forget

we can go

or we can stay

we can either speak

or we can be silent

but to see is a word without alternative like breathing”